Speak to anyone attempting a major commercial building project and they will tell you that planning laws and processes in the UK are complex; talk to someone involved in the development M62 Birchwood services and you may well be met with a heavy sigh.

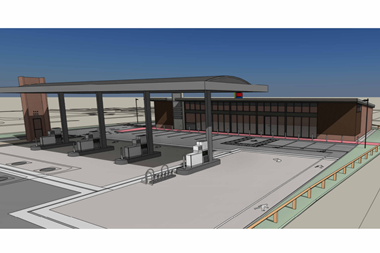

The £75m motorway service area (MSA) proposed by Extra would sit by Junction 11 of the motorway to the north-west of Huddersfield and comprise a 100-room hotel, parking for 536 cars, a filling station with 12 bays, 16 EV charging spots, a children’s play area, a main facilities building with food offerings, and various other amenities – though many details are yet to come.

Around 300 additional jobs would be needed for construction alone, with 200-250 permanent roles created in the local area once the MSA is up and running.

Yet despite the services being officially proposed six years ago, ground has yet to be broken on the project.

Warrington Borough Council’s (WBC) planning officers supported the plans when they were submitted in 2019, but the council itself had other ideas, and refused permission over concerns the services would adversely affect the green belt.

Proposals to build on green-belt land clearly warrant proper consideration, but the area in question is hardly a utopian vista. In addition to the motorway, a distribution centre for Walkers crisps, an InPost warehouse, HMP Risley and a used truck dealership are all within a stone’s throw of the plot, while planning consent was recently granted for a 9.6-hectare solar farm to be built on a nearby site previously occupied by a landfill.

The epic continues

Back to the MSA, Extra appealed the council’s refusal notice, and WBC seemingly had a change of heart, as it voted not to provide evidence to defend the refusal. The matter nonetheless went to the Planning Inspectorate for a four-day (five if you include the site visit the Inspectorate made) hearing, which eventually ruled in Extra’s favour in May 2022.

Three years on, and spades remain in vans and diggers on flatbeds, as the planning process is still incomplete.

Over the past 12 months alone, 20 separate planning applications relating to this MSA have been made to WBC, often relating to “discharges of conditions” – IE the developers demonstrating they have carried out required tasks such as conducting a badger survey.

Also included in this year’s batch of files is a fish survey and subsequent 16-page report, necessitated because a brook needs to be diverted for the MSA to be built. An investigation into whether great crested newts are present on the land in question was also carried out; this resulted in a Great Crested Newt District Level Licensing Impact Assessment & Conservation Payment Certificate being issued.

Undertakings such as these are required by national planning laws rather than local councils, but they are nonetheless indicative of just how onerous the process of getting a project like this off the ground is.

You ain’t seen nothing yet

Around 60 documents were submitted to the council for the initial 2019 application. Many revisions, appendices and addenda were added to this roster, with a total of 116 files uploaded during the course of the initial application for outline – not full – planning permission

These documents will have been compiled over days and weeks of site visits, meetings and keyboard-bashing sessions by skilled, specialised professionals such as planning consultants, ecologists, travel-pattern analysts, archaeologists, climate bods, and so on – each on a decent wage. And some reports will presumably have been looked over by lawyers on hourly rates that would raise a few well-groomed eyebrows.

Drilling down into the details of the initial application, The Non Technical Summary of the Environment Statement is a mere tiddler at 25 pages, whereas the main Environmental Statement compiled on Extra’s behalf and submitted to WBC is 264 pages long – but this is only the beginning.

The Environmental Statement Part 2 is split into a series of 13 ‘Technical Papers’. To take a few examples:

- Technical Paper 4 is on Landscape and runs to 194 pages.

- Technical Paper 5 is on Ecology and Nature Conservation and runs to 268 pages

- Technical Paper 7 is on Geology and Ground Conditions and runs to 204 pages. This is not to be confused with Technical Paper 7, Addendum to Environmental Statement on Noise and Vibration, which covers 96 pages.

- Technical Paper 8 – Air Quality, Odour and Dust – also comes in at 96 pages; this paper had six revisions.

- Technical paper 9 required 115 pages to cover Archaeology and Cultural Heritage.

- The Climate Change Technical Paper 13 (Revision F) is a weighty 245 pages.

Away from the Technical Papers:

- The Information To Inform A Habitats Regulations Assessment document is 39 pages.

- The Statement of Community Involvement is 56p.

- The Peatland Ecological and Construction Management Plan is 36 pages.

- The Energy Statement is 70 pages, the Staff Travel Plan 50 pages, the Need and Alternative Sites Assessment 103 pages; the Arboreal Impact Assessment 40 ; the Utilities Assessment 93; the Landscape and Visual matters and Openness of the Green Belt report 29 ; the Expert Evidence in respect of Biodiversity Volume 1 is 39 pages (Volume 2, Appendices to Proof is 26 pages); and on, and on, and on, ad nauseum.

This, to put it bluntly, is utter utter madness.

Roads, and good intentions…

There will unquestionably be good individual reasons for each of these reports. The road-infrastructure changes necessitated by a new MSA are not to be taken lightly, for example. Similarly, it is understandable why authorities would want to know that developers are aware of the ground conditions of a site where major works are proposed.

When taken in the round, however, the requirements for big developments such as a new MSA are preposterously onerous, and in dire need of rationalisation.

Perhaps combining a few documents would help – is there really any reason why the air quality, odour and dust report could not be combined with the noise and vibration report? Could the habitats of newts, fish and badgers not be assessed in one wildlife paper? Or perhaps planning laws should stipulate legally binding word counts, a maximum number of pages, or Formula 1-style cost caps.

Experts in this field will no doubt offer entirely rational explanations as to why such suggestions are naïve, but it is not unreasonable assess processes by their outcomes, rather than whether they offer box-ticking compliance.

In this instance, the outcome of six years’ work undertaken by scores of people at great cost amounts to nothing more than paperwork unless you count the jobs required to run the processes themselves – but that’s not true economic growth. Meanwhile, the 250 jobs that would be created by the services are still just ideas, rather than tangible positions that offer fresh employment to all the working-age adults of a small village, creating new taxpayers in the process.

Extra’s bosses can take heart that they are not working on the Lower Thames Crossing, which has cost £250m for planning alone; or the reopening of the 3.3-mile Bristol and Portishead train line, which has required 79,187 pages of planning documents, with 17,912 of these dedicated to environmental matters alone.

Ultimately, the costs involved in planning are borne by citizens, either via the taxes that pay officials’ salaries, or the higher prices MSA operators must surely charge to recoup the expenditure made over the course of acquiring necessary permissions.

English planning regulations have been allowed to spread like knotweed, smothering progress and slowing growth to a crawl. It’s high time someone dug out the shears.